Christopher Mitchell

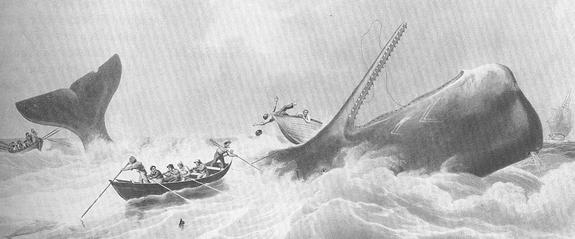

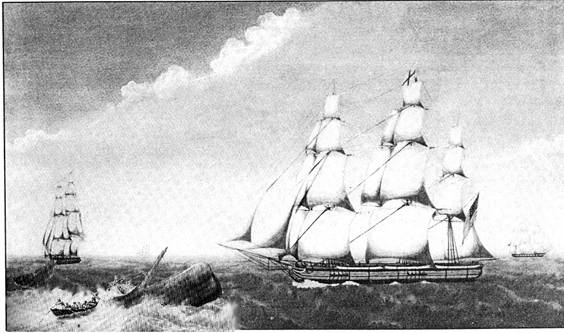

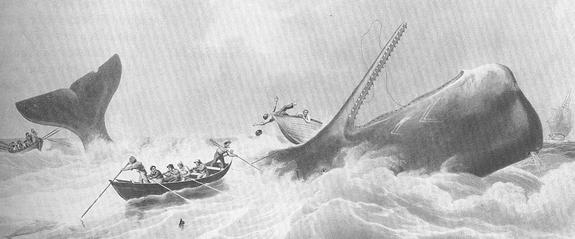

Our story takes place on the Christopher Mitchell. This is a drawing of the Christopher

Mitchell with a superimposed picture of an attack on a sperm whale.

The most intriguing aspects of this story are based

upon letters from the US Consulate in Paita, Peru, newspaper articles from

Rochester, N.Y., other newspaper articles including an interview with the First

Mate of the Christopher Mitchell, and the book Whale Hunt by Nelson Cole

Haley relating the account as given by Captain Thomas Sullivan and other

members of the crew of the Christopher Mitchell during a “gam” (chance meeting)

at sea. As you read, keep in mind that what happened to George Johnson and his

impact on the crew of the Christopher Mitchell are based on evidence found in

these sources.

The portrayal of characters, other than George

Johnson, is designed to fit the story. So, while the character names are

true, their portrayal is not. The First, Second, and Third Mates, and the

boatsteerers (also known as the harpooners) were determined from order in the

ship’s log and partially verified by the account in the Rochester, New York, newspaper article.

A whaling voyage in 1849 would take, on the average,

about 3 years. The ship would be provisioned for months at a time and need to

stop at various ports for more provisions only as required. Months may be

spent on the ship without ever setting foot on land.

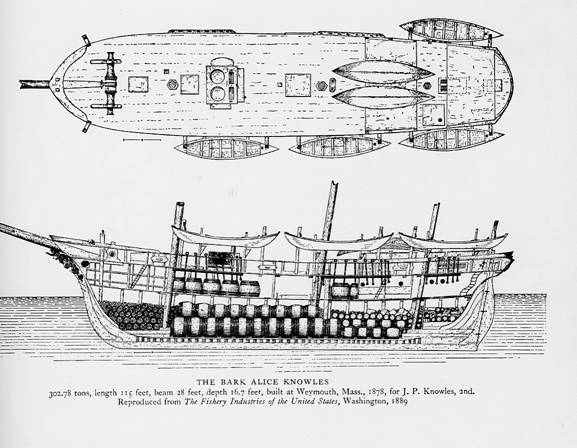

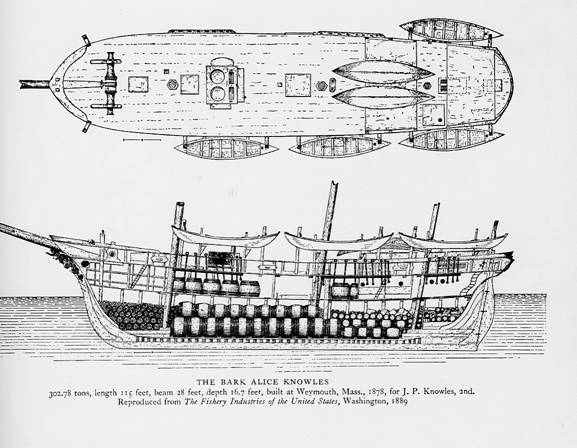

The bark Alice Knowles has much the same construction as the

Christopher Mitchell. This ship was 302 tons, 115 feet long, 28 feet wide, and

17 feet deep. It was built at Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1878. This diagram

was originally taken from The Fishery Industries of the United States, Washington, 1889. The Charles W. Morgan, another ship of this era, can be seen and toured

at Mystic Seaport, Connecticut.

The whale ship carried 3-6 whaleboats which were used

to attack the whale. Two of these were kept as spares to be used when the

others were damaged, sometimes due to weather but more often due to encounters

with whales.

The boats were cramped, as they contained all the equipment

required to attack a whale, to navigate back to the ship should its position be

lost, to deal with damage to the boat, and to perform the job of maneuvering on

the water. Into this, 6 sailors would take their positions, five as rowers and

the First, Second, or Third Mate who would steer.

The harpooner, or boatsteerer, was furthest forward and

rowed to starboard. Next was the bow rower who rowed to port. Next was the

midships position which rowed to starboard. Then, on alternating sides were

the tub and stroke or after oars. A hole in the second seat back from the bow

received the mast and yard. These, however, were often carried lengthwise in

the boat. Five oars about twelve feet long were placed in the boats and

paddles were placed at each of the positions as well. A nineteen-foot

steering oar would be laid across the seats. When the harpooners had

completed their preparations, a tub of rope was also placed in each boat just

in front of the stern-most seat. A smaller tub with about 75 fathoms, or 450

feet, of line was also in the boat. This was the towline used in bringing

whales to the ship. Three neatly sheathed harpoons, or irons, were placed in

the bow along the starboard gunwale of the boat with each shank resting in a

notch. Three lances would be neatly placed on the opposite gunwale in the same

fashion. With the wooden shaft, a lance was about eight feet in length. Each

boat had a small water keg, and another long narrow one with a few biscuits, a

lantern, candles and matches within. There was a bucket and large ladle for

baling, a small spade, a flag, two knives and two small axes. A rudder hung

outside by the stern. In all, there were forty eight articles, and at least

eighty-two pieces according to some accounts.

1, 2, 3, 4, & 5 indicate rowing positions for harpooner,

bow, midship, tub and stroke oarsmen

6. Steering

oar strap & brace

7. Lions

tongue

8. Mast

and sail

9. Loggerhead

10. Water breaker, piggin, and

lantern keg in after cuddy

11. Standing cleats (2)

12. Mainline tub & line

13. Spare line tub

14. Sheath knives (2)

15. Hatchets (2)

16. Oarlocks (4 regular and 1

double tub)

17. Paddle for each oarsman (5)

18. Peaking cleats – one for

each oarsman

19. Lances (sheathed heads 4)

20. Spare harpoons (3)

21. Working harpoons in the

crotch

22. Hinged mast partner

23. Boxed mast step

24. Centerboard case

25. Shroud cleats (2)

26. Line stops (2)

27. Clumsy cleat – notch for

harpooners knee to larboard

28. Kicking strap

29. Hoisting rings or shackles

30. Boat warp or pointer

31. Box warp or stray line (part

of main whale line)

32. Chock pin

The forecastle was home for the common sailor. The

boatsteers, idlers, mates, and Captain bunked in the aft of the ship. The

forecastle had one entrance and no portholes. An average sized man would need

to walk with head bowed to avoid hitting his head on the beams. Bunks were

placed along the hull. Chests found room on the floor of the forecastle. What

room was left would be used as meeting place for eating, sharing yarns, and

passing the time during stormy weather.

The quarters furthest aft belonged to the Captain. Those

just forward of that, were for the Mates, harpooners, and idlers. These had

single entrances and portholes. While the space was nearly as cramped as in

the forecastle, it was a privilege to have an aft berth. Not only was the ride

better, but the food was often of a better quality as well.

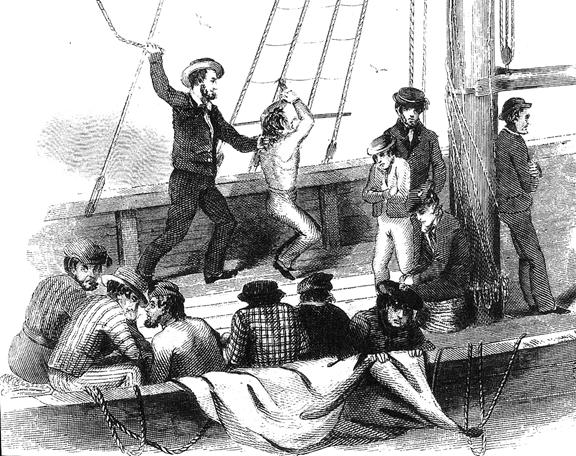

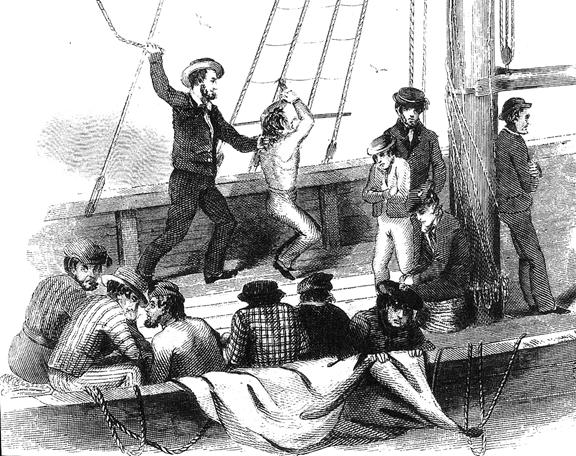

Attacking a whale was dangerous business. In this picture,

the boat in the front is attacking the whale which has rolled leaving his most

vulnerable spot open to the lance wielded by the mate. The harpooner is at

this point in the stern of the boat using the steering oar. When the whale was

mortally wounded, it would spout blood from the blowhole in the top of its

forehead. Once taken, if the wind were not with the ship, the whale would be

towed to where the ship waited.

The head of the sperm whale is a marvel. The top half,

called the case, contains pure spermaceti. The bottom half, called the junk,

contains spermaceti mixed with fibrous matter. The lower jaw contained the

teeth which fit into indentations in the upper jaw.

Flogging was a common punishment. Some Captains used it to

excess which often times caused more problems than it resolved. When given,

all the crewmen were usually required to watch.

Standing watch at the top of the masts was a lonely and

boring business. The man, whose job was to watch for whales, had time to think

on all sorts of matters and often had to actively fight sleep. The watch was

usually a two hour job. The lookout was reached by climbing the rigging and

then crawling up the ropes that stretched from the mast to the edge of the

platform. As he stretched over the edge of the platform, he would grip the

ropes that rose upward from the its edge and then pull himself completely up.

The lookout would stand within a ring that was about chest high. In bad

weather or when dozing, it would be all that kept him from a disastrous fall to

the deck or into the sea.

The main hatch opened to the blubber hold. This compartment

held the blanket pieces cut from the whale. In the heat of the summer or when

hunting the line (equator), it was unbearably hot and quickly turned the

blubber to what was called stink for obvious reasons.

A special thanks is extended to the Nantucket Historical

Association and their wonderful library. Also, a thanks to the Mystic

Seaport’s whaling display and their guides on the Charles W. Morgan, a ship of

the same vintage as the Christopher Mitchell. Research in Rochester, New York, was facilitated by Ms. Ruth Tiano.